The train was bound for Liverpool, where its passengers

(mostly soldiers of the 7th Battalion of the Royal Scots) would be loaded onto

ships and sent onwards to Gallipoli, where they expected to encounter

challenging conditions and fierce fighting against Ottoman forces.

Little did the men on board realize, however, that the vast

majority of them would never make it beyond Gretna Green.

The train on which they travelled was about to become part of one of the worst rail disasters of all time.

The declaration of war in 1914 made the movement of freight

and troops of paramount importance to Britain.

So vital were the railways, indeed, that the government

immediately seized control of most of them and pressed into service every car

they could get their hands on, including old rolling stock that had been given up

for scrap in previous years.

New wagons were built quickly and cheaply to keep Britain

moving.

The flow of these wagons and the engines which pulled them

was controlled by signalman in signal boxes situated at every vital junction

and crossing.

By pulling levers these men could switch points to direct

trains from one track to another and activate signals which would instruct

trains to proceed, wait in a siding, or reverse as necessary.

The signal box closest to Gretna Green was the Quintinshill

signal box.

Although usually manned by only a single signalman there

were actually two present at the time of the disaster.

George Meakin was the night signalman.

After being relieved by his day shift colleague James

Tinsley he hung around in the box reading a newspaper while Tinsley set himself

up for the day.

This handover also happened later than was scheduled.

Technically Meakin should have handed over to Tinsley at 6:00am...but there was an informal agreement in place between day and night signalman whereby the night signalman on duty would often work up to half an hour late so that the day signalmen that would relieve them wouldn't have to get up so early.

Thus it was actually 6:30am when Tinsley arrived and took control of the box.

This half-hour difference seemed of little consequence to

the signalman themselves, but it would be one contributing factor in what

happened next.

Tinsley would be controlling a relatively simple section of

track.

It consisted of two lines one running towards Carlisle,

which was referred to as the "up" line, and one running towards

Glasgow, which was referred to as the "down" line.

Each of these lines also had a siding.

This would allow slow trains to pull off the main track and

allow faster express trains to bypass them and get underway.

It was also possible to move trains between the up line and

the down line using a connecting section of track.

At the time of the disaster the siding on the down line was

occupied by a parked goods train.

A local train on the down line needed to move aside so that

an express train could get by.

Night signalman Meakin was well aware that it couldn't pull

into the occupied siding, and so instead he had it reverse from the down line

onto the up line.

This freed up the down line and let the express train get past...but left that local train parked on the up line.

A train consisting of empty coal wagons was waiting to use

that up line.

Meakin, still in control of the situation, sent that train

into the siding and ordered it to wait there.

It was at this point that Tinsley took control of the box

and ushered through one express train that was waiting on the down line.

As the down line was clear this train passed through without

incident.

Then, seemingly forgetting about the local train parked on

the up line, Tinsley signaled to a troop train waiting to pass through the up

line that it was clear to proceed.

This moment of absent-mindedness is all the more alarming

given that Tinsley arrived for his shift that day riding on board that local

train.

He had only hopped off the engine minutes before.

Now its presence completely slipped his mind.

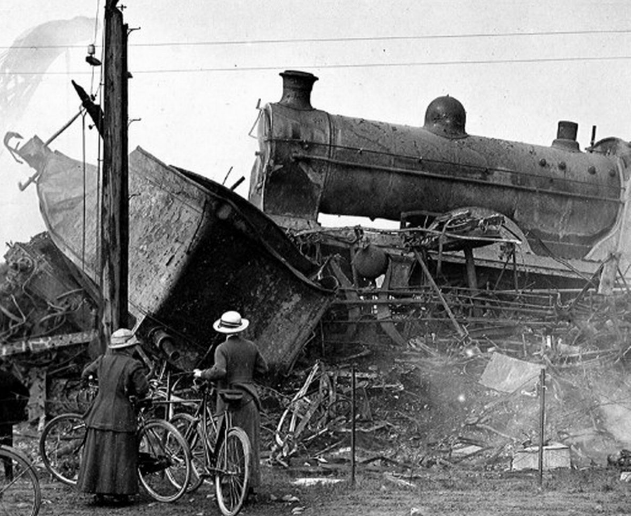

The troop train surged along the up line and, with a

thunderous crash, smashed into the local train, sending several of its cars

spilling from the track.

Many were injured and killed by this collision, but the

situation was still to worsen.

Another express train was already inbound on the down line.

It was too late for the signalman to stop it.

The express train entered the down line, plowed into the

scattered wreckage, and itself derailed.

Now there were three trains smashed together and scattered

across the tracks.

Dozens of people lay dead, some of them hit by the express

train after having evacuated the troop train and local train.

Many more were injured or trapped in the wreckage...but still the worst was yet to come.

The rickety troop train - pressed into service specifically

for the war effort - was built from cheap wood and lit by gas-powered lanterns.

These swiftly started a fire which swept hungrily through

the wreckage, consuming those who had survived the collision.

Rescuers worked frantically to free their friends and fellow

soldiers from the wreck, but in many cases it was simply impossible.

There wasn't time to do so before the smoke and flames

reached them.

There are many stories of impromptu amputations that were

carried out on the spot to free trapped soldiers.

Witnesses also report that, where rescue was impossible and

flames were approaching, officers shot their own men in order to spare them the

pain of burning alive.

Doctors and firefighters from Gretna Green soon arrived at

the site of the collision.

They were met with an apocalyptic scene of death and

destruction.

Over 200 people had died in the space of mere minutes, and

the fires which burned through the wreckage raged for an entire day.

Every single wagon - apart from six which had detached at

the moment of collision and rolled back along the track - was entirely consumed

and every ounce of coal on board the train was burned up by the flames.

The vast majority of casualties were from those on board the

troop train.

226 people died in the collision, and 215 of them were

soldiers.

These numbers are, it should be noted, approximate: the fire

was so intense that some bodies could not be identified, and some were entirely

cremated by the flames.

Taking into account both deaths and injuries, the 7th

battalion was left utterly devastated.

Approximately half of the entire unit had been on board the

train: 498 soldiers.

Only 62 of those arrived in Liverpool unscathed.

Given the trauma that they had endured, and the depletion in

their numbers, the men were sent straight back to Edinburgh, with only a

handful of ranking officers required to board a ship and sail for the front.

Most of the dead had come from the town of Leith.

It was said that there was not a single household in that

community who did not know at least one of the dead.

This emotional shock was no doubt compounded by the fact

that so few bodies could be positively identified.

The majority of the dead was simply too badly burned.

A funeral procession through Leith carried the bodies to

their final resting place: Rosebank Cemetery.

Thousands of soldiers and civilians lined the route in order

to pay their respects to the dead, who were then interred in a mass grave.

Even as the bodies were being buried an investigation was

launched.

Its findings were decisive: the fault lay with the two

signalmen, Meakin and Tinsley.

They came under fire for the unofficial tweaks they had made

to their shift schedule.

It was perfectly common for the night signalman on duty to

work half an hour late to save the day signalman from getting up too early, but

it certainly wasn't officially allowed.

To avoid getting into trouble Meakin wrote down his notes

for the extra half hour he worked on a piece of scrap paper so that Tinsley,

when he eventually did arrive, could copy them out into the logbook in his own

handwriting, making it seem as though he'd arrived at exactly the right time.

Thus, when Tinsley should have been concentrating on the

complex situation on the train lines, he was actually more focused on updating

the logbook to ensure that he didn't get into trouble for sleeping late.

This distraction might have contributed to him forgetting

the presence of a train on the upline - the most egregious error which

contributed to the disaster.

But Tinsley alone wasn't to blame.

During his shift Meakin had also neglected to place a safety

collar on one of the signals.

The collar would have physically prevented Tinsley from

giving an incorrect signal.

The two men were found guilty of culpable manslaughter.

Meakin was sentenced to 18 months in prison, while Tinsley

was given three years with hard labor.

Both prisoners were, however, released after just one year -

a sentence which might seem shockingly light by today's standards.

However this accident occurred during wartime, when every

available man was needed to serve King and country.

The death of more than 200 soldiers in a terrible accident

was more forgivable in a context where thousands were slaughtered each and

every day in the trenches.

Indeed, after their release from prison, both men were

re-employed to work on the railways, and went on to have long and relatively

successful careers.

Meanwhile a memorial was raised to the dead by public

subscription.

It stands to this day in Rosebank Cemetery in Leith.

Upon it are listed the names of the dead - those men who, despite being brave enough to fight for their country, died before even reaching the battleground. (The Quintinshill Rail Disaster)

Post a Comment

Post a Comment