Fascinating Horror - On the 28th of August, 1988, 300,000 people gathered at the US Air Force Ramstein Air Base in Germany to watch an air show featuring a demonstration by the Italian Air Force.

During the performance, a mid-air collision would result in what

was at the time the deadliest air show disaster in history – the emergency

response to which would highlight a fundamental breakdown in cooperation

between the US and German authorities.

Background

In the aftermath of World War II, the USA decided that, due to rising tensions with the Soviet Union, they would need a greater air defence presence in Europe.

They wanted to move their vulnerable fighter units away from East

Germany.

As part of a NATO expansion programme, France agreed to offer

space in their zone of occupation in West Germany, in Rhineland- Palatinate.

Construction of the Ramstein Air Base began in April 1948, near

the city of Kaiserslautern, and it was opened on the 1st of June 1953.

Complete with family housing, headquarters, schools, cinemas,

administrative offices, and a commissary, it was a massive air base covering

over 3,000 acres.

It was originally made up of two separate bases, The Ramstein Air

Station and the Landstuhl Air Base, but these were joined together after the

German government constructed the A6 Autobahn which completely cut off access

to the main gate of the Landstuhl base.

This was seen by some as an example of the ways in which the

German and American authorities often failed to communicate.

Meanwhile, in 1961, the Italian Air Force created a department

whose specific purpose was to form a national aerobatic team - the Pattuglia

Acrobatica Nazionale Frecce Tricolori.

They replaced unofficial teams that had been performing since the

1930s, and were the largest aerobatic patrol in the world.

A famous part of their display was to trail green white and red

smoke in a representation of the Italian flag – an appropriate symbol given

that part of their name - Tricolori, or “Three colours” – was a reference to

the flag.

Only the best pilots, with more than 1,000 flight hours, were

chosen to be part of the Frecce Tricolori.

Despite this, and the fact that the squad was purely

demonstrational, it was still a very dangerous job.

Within the first six months of the department’s existence, there

had been four accidents, with two members of the team dying as a result.

Another famous formation was known as “The Pierced Heart”.

To complete this manoeuvre, two groups of aircraft flew in

opposite directions to form a heart shape, which was then pierced by a lone

aircraft.

The Ramstein Air Base Disaster

During the afternoon of Sunday the 28th of August, 1988, a huge crowd of 300,000 people had gathered at the Ramstein base to watch the Frecce Tricolori.

Air shows had become a huge fundraiser for the base.

Some of the units located there were, in fact, deployed for the

day working on ice cream trucks to help raise money from the vast crowds.

The weather on the day was perfect for flying - clear and sunny.

The Frecce Tricolori began their demonstration and performed

several complex manoeuvres to the general delight and admiration of the crowd.

It was all building to the climatic performance of The Pierced

Heart.

The manoeuvre initially went well.

Two groups of planes formed a heart shape in the sky above the

airbase, approaching one another for a close pass at the lower point of the

heart at 3:44pm.

The plane that should have subsequently “pierced” the heart,

however, approached too low and too fast.

Before the two groups of planes could clear one another, this

plane, the call sign of which was “Pony 10”, smashed into them at high speed,

just 45 metres (or 150 feet) above the ground.

Three aircraft were involved in the collision.

Pony 10 crashed into the runway below, exploding into a violent

fireball and showering the watching spectators with burning fuel and debris.

The largest parts of the plane came to rest against a refrigerated

ice cream trailer.

Meanwhile, one of the other aircraft that Pony 10 had hit crashed

directly into a medical evacuation helicopter that was parked on the ground.

The third aircraft exploded in the air, raining down more debris

on the crowd below.

Several planes remained in the air, having narrowly escaped being

involved in the collision.

They regrouped and flew to Sembach Air Base, around 30 kilometres

(or 19 miles) away.

As they left the area, the situation on the ground was chaotic.

The crowd had been showered with debris, killing 28 people

instantly.

Two of the three pilots involved in the collision had died on

impact.

The third had managed to eject, but his parachute had not opened

and he had also died when he hit the ground.

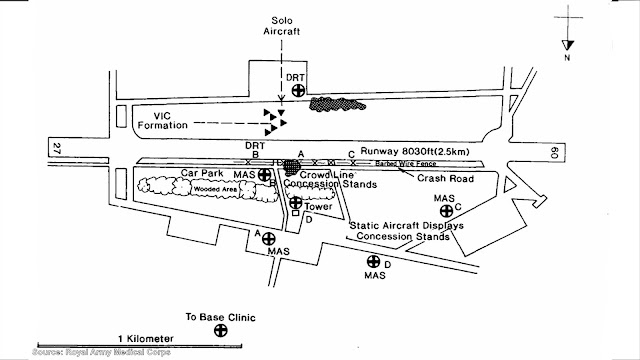

American firefighters and ambulance personnel arrived on the scene

just two minutes after the collision.

It became quickly apparent, however, that the US vehicles (which

usually only served the base itself) did not have sufficient medical equipment

to cope with a disaster of this scale.

Calls were placed to German emergency services, but ambulances

that were despatched were held up at the entrance to the base.

German vehicles were not normally allowed to enter, and it took

some time before permission could be obtained to allow them entry to attend to

the wounded.

German medivac helicopters started arriving at 4:10pm, but it was

nearly an hour after the collision, before enough ambulances had arrived to

treat the injured.

The delay in getting adequate resources to the site was also

compounded by the chaotic nature of the immediate response.

A doctor who was present at the time later recalled the scene: “We

are searching for burnt patients that are pulled and transported unaided away

from us by the Americans… Not all the injured people are transported away by

helicopter or ambulance.

There is total chaos around us and some of the injured are even transported on pickup trucks that are not leaving (via) an emergency exit, they are driving beside the drifting visitors.” The confusion wasn’t limited to the scene.

The German authorities still had little idea of the scale of the

disaster even an hour after the collision.

One medic on site later described the confusion: “It was not

possible to find an officer in charge, a director of operations or even a

contact person… Asking several action forces, paramedics, police officers

nobody could name a director of operations.

I was asking for a managing paramedic of the operation to coordinate the evacuation. But there was none.”

Many patients were rushed off the base by American personnel, who used wooden planks rather than waiting for stretchers, and carried patients in trucks or other vehicles rather than waiting for ambulances.

While this allowed casualties to be transported more quickly, it

also meant that they could not receive treatment during transport… and, worst

still, American drivers who were unfamiliar with the area risked taking a

circuitous route or transporting patients with severe injuries to the wrong

hospital.

Equally, hospitals which had been given little information about

the disaster, were unable to prepare for the influx of severely injured

patients.

A German paramedic later reported the conditions they found at one

nearby medical centre: "When I arrived in Landstuhl, severely burnt people

lay on wooden planks and no paramedics were there.

After I aided an injured person and left her with a hospital nurse that attended us at the flight, I was treating several injured people at the helicopter landing zone at the military hospital and did not see even one American medic there."

At 6:30pm a bus full of injured people (including some with severe burns) arrived at a hospital in Ludwigshafen, around 80 kilometres (or 50 miles) away.

There was no paramedic present, just a non-German-speaking driver

that did not know the area, and had spent hours desperately searching for a

hospital.

In all, 67 spectators and three pilots died in the accident, and

500 people required hospital treatment.

The Aftermath

In the aftermath of the disaster, questions were asked both about the initial cause of the accident, and the response to it.

Why had Pony 10 come in so low and so fast for the final part of

the Pierced Heart manoeuvre? While some theorised that it could have been due

to a technical issue or even sabotage, there was no evidence to support this.

The most likely cause of the accident, it was concluded, was pilot

error.

The response from the US military and the German civil authorities

was criticised.

Investigations revealed that, for much of the accident, it was

completely unclear who was in charge.

Communication throughout was extremely poor – sometimes relying on

amateur radio operators who happened to have been at the air show to transmit

vital messages.

The US military prioritised transporting patients over providing

first aid, and in many ways German and American protocols were so different

that a unified response was impossible.

Many air shows across Europe were cancelled in the wake of the disaster,

and it was three years before another air show of the same scale would take

place in Germany.

During that time rules were put in place to establish a much

larger minimum distance between aerobatic displays and crowds, and manoeuvres

oriented toward any crowd were banned outright.

Because of these changes, air shows across Europe are

significantly safer than they were before the disaster.

Today there stand two memorials to the 70 people that lost their

lives as a result of the disaster – one accessible to the German public just

outside the west gate of Ramstein Air Base, and a separate memorial inside the

base itself.

SOURCES:

- "Ramstein 1988: Death falling from the clear blue sky" by P Huber, published by Austrian Wings, August 2018. Available via: https://web.archive.org/web/20180901145758/https://www.austrianwings.info/2018/08/ramstein-1988-death-falling-from-the-clear-sky.html

- "Aug. 28, 1988: Ramstein Air Show Disaster Kills 70, Injures Hundreds" by D Dumas, published by Wired, August 2009. Link: https://www.wired.com/2009/08/0828ramstein-air-disaster/

- "West Germany Hellfire from The Heavens" by James O Jackson, published by Time, September 1988. Available via: https://web.archive.org/web/20070318005720/http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,968416,00.html

Post a Comment

Post a Comment