Fascinating Horror - On the 29th of May, 1914, two ocean liners collided in heavy fog in the St Lawrence estuary on the east coast of Canada.

The collision resulted in the loss of over 1,000 lives on the RMS Empress of Ireland; a death toll comparable to that of the sinking of the RMS Titanic two years earlier.

The disaster was the fourth largest ever maritime loss of life in peacetime.

Background

The period from the mid-1800s to the early 1900s is often recognised as the golden age of sailing.

Maritime technology advanced rapidly during this time, and there was a huge demand for the manufacture of new ships – demand driven by increasing global trade, increasing immigration, and latterly by the advent of World War I.

Commercial shipping companies rapidly expanded their fleets.

Canadian Pacific Steamship was a major company providing passenger travel between the United Kingdom and Canada.

They commissioned a ship to be built by the Fairfield Shipbuilding and Engineering Company in the Scottish shipyards of Govan.

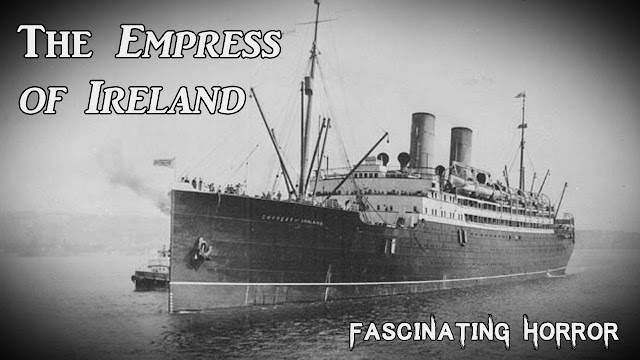

This ship was to be known as the Empress of Ireland.

Work started on the Empress in April 1905, and it was launched in January of the following year.

The dimensions and power of the vessel were impressive.

The ship was of steel construction, and was 174 metres (or 570 feet) long.

It had four large decks which were divided into passenger cabins and spaces for entertainment.

The whole thing was driven by a huge pair of twin propellers, which were turned by quadruple-expansion steam engines.

These gave the Empress a cruising speed of 18 knots, and an average trans-Atlantic journey time of less than four days.

Safety was also taken into consideration.

The hull was divided into eleven compartments, which could be closed to water via a total of two-dozen watertight doors.

The sinking of the Titanic in 1912 also lead to a worldwide revision of lifesaving equipment, which prompted the Empress to switch from wooden lifeboats to sturdy steel ones.

The ship had space for 1,542 passengers.

First class accommodation was available for 310 passengers, and was located primarily on promenade decks adjacent to the dining room, library and glass-domed music room, which came complete with its own grand piano.

The lower promenade and main decks provided cabins for 468 in second class.

Up to 764 cabins for third class and immigrant travellers were located in the forward portion of the ship.

A primary function of the Empress of Ireland was to serve the Irish community who settled in Canada, and over its eight-year history, the Empress transported passengers between Liverpool, Ireland, and Canada.

Canadian destinations would vary – Quebec City in late spring, summer and autumn, then Halifax in Nova Scotia and Saint John in New Brunswick for winter and early spring.

The Sinking of the Empress of Ireland

On the afternoon of the 28th of May, 1914, the Empress of Ireland left eastbound for Liverpool on its last journey from port at Quebec City.

The captain for this voyage was Henry George Kendall – a man who had just been promoted to take charge of her that month.

There were 420 crew and 1,057 passengers on board.

The numbers in first class were small on this particular voyage; and the bulk of second and third class consisted of a large party travelling to attend the 3rd International Salvation Army Congress in London, as well as some North American and Canadian former immigrants travelling to visit family and friends in Ireland and mainland Europe.

The day after departure, the Empress of Ireland arrived at Pointe-au-Pere.

A specialist river pilot who had helped navigate the narrower parts of the St Lawrence River disembarked, his job completed, and the ship resumed on an eastbound course.

Even at midnight visibility was good – crew on board the Empress could easily see approaching hazards.

Among these hazards was the Norwegian cargo ship the SS Storstad, which was approaching westbound.

As long as visibility remained clear, the two ships would be in no danger of colliding.

Before they could safely pass one another, however, a thick fog descended over the river mouth, drastically reducing visibility.

Both ships starting using fog whistles to advertise their location… but it was no good.

Just before two o’ clock in the morning the Storstad loomed out of the fog and smashed into the Empress’s starboard side.

The damage to the Empress was catastrophic – a large puncture led to rapid flooding of the lower decks where the majority of second and third class passengers were accommodated.

With both ships still entangled, Captain Kendall anticipated that the Empress was likely to sink imminently unless something was done.

The gaping hole had to be closed without delay.

Kendall used a megaphone to call out to the Storstad to keep her engines running, and to keep driving forward so that she would plug the hole in the side of the Empress.

Despite this, the momentum of the two vessels and the current of the St Lawrence river combined, and swiftly pulled the two ships apart.

With nothing plugging the gaping hole in her side, it was now almost inevitable that the Empress would sink.

Water gushed in through the breach so quickly that there was no opportunity to seal the watertight compartments.

The ship leaned rapidly to starboard, allowing more water to enter portholes that had been left open for ventilation.

Lower deck passengers and crew had no chance of escape, and were the first to lose their lives in the disaster.

Those on the upper decks would ordinarily have had a better chance of escape via the lifeboats, but the angle of the Empress as it submerged was steep.

Most lifeboats that were launched smashed against the ship’s side, throwing their occupants overboard into the icy water.

Within minutes, electrical power failed, and the sinking ship was plunged into darkness.

As the Empress continued to lean to starboard, hundreds of passengers and crew climbed out onto the port side.

This offered only a temporary reprieve – within fifteen minutes of the collision, the Empress up-ended and sank completely.

The loss of life during the sinking was incredible.

The loss of records makes the exact figure difficult to ascertain, but by most accounts at least 1,014 people lost their lives when the Empress of Ireland sank.

The Storstad spotted some survivors in the water, and a rescue operation was quickly arranged to pluck them out of the water using its own lifeboats.

Two other ships, the Eureka and the Lady Evelyn, were alerted by the Pointe-au-Pere coastguard, who had received a distress call.

The Eureka arrived at the scene at 3:10am, and the crew rescued around 150 people either from the water directly or from the few lifeboats that were successfully despatched from the Empress.

Survivors were taken to Rimouski Wharf for immediate medical care.

By the time the Lady Evelyn arrived, no survivors could be seen in the water, but it assisted by transferring the 200 survivors collected by the Storstad, and removing 133 bodies.

Captain Kendall was among the survivors.

He had been thrown into the water from the bridge as the Empress began to submerge, but was pulled onto a lifeboat by crew.

He and his men proceeded to rescue as many passengers as they could, ferrying between the Empress and the Storstad until so much time had passed that (given the near freezing conditions), any further efforts would have been futile.

Among the passengers who died were Laurence Irving (the son of Victorian stage actor Sir Henry Irving) and his wife; the former member of the House of Commons Sir Henry Seton-Karr, and Gabriel J Marks, the Mayor of Suva.

In second class, 167 members of the Salvation Army passed away during the disaster.

The Aftermath

An 11-day inquiry was held in Quebec, headed by Lord Mersey who had previously contributed to the investigation into the sinking of the Titanic.

Many lines of inquiry were followed: had the crew and command been adequate? How had visibility changed as fog descended? Had the fog whistles been used correctly to indicate the direction of each ship? And, importantly, were either Captain Kendall or the officers of the Norwegian ship responsible for the disaster? The inquiry established that lights and whistles were used appropriately, and that when the ships were clearly visible to each other, they were on course to pass safely, but that the Storstad made a last minute directional change to starboard after the fog had descended, and therefore caused the collision.

Following the inquiry, a court ordered owners of the Storstad to pay two million Canadian dollars as compensation for silver bullion lost on the Empress of Ireland.

Given the relatively shallow depth of water, salvage was considered possible, and the safe, valuables and mail from the Empress of Ireland (along with some human remains) were eventually retrieved by divers.

This accident was one of the biggest disasters in the history of ocean liners, with a death toll of over a thousand.

However, the disaster did not receive the same amount of media attention as the loss of the Titanic in 1912.

The sinking of the Empress of Ireland did prompt some changes in ship design.

The Storstad had featured a prow that was more prominent below the waterline, ensuring that in the event of a head-on collision, most damage would be done below the water.

After the disaster, ships were designed with prows that were more prominent above the water, so that damage in the event of a collision would be concentrated there.

To this day the shipwreck of the Empress lies at the bottom of the Saint Lawrence, marked by various monuments on dry land between Rimouski and Pointe-au-Pere, maintained in memory of the thousand lives that were ended when the Empress of Ireland sank beneath the water on the 29th of May, 1914.

SOURCES:

- "Disaster at Sea: Shipwrecks, Storms, and Collisions on the Atlantic" by William H Flayhart, published by WW Norton & Company, 2005. Link: https://wwnorton.co.uk/books/9780393326512-disaster-at-sea

- "The Collision between the S/S Empress of Ireland and the S/S Storstad" by Marion Kelch, published by Norway Heritage, February 2005. Link: http://www.norwayheritage.com/articles/templates/great-disasters.asp?articleid=99&zoneid=1

- "Report and evidence of the Commission of Inquiry into the loss of the British steamship Empress of Ireland..." by John C Bigham, published by J de L Tache, 1914. Available via: https://open.library.ubc.ca/collections/chung/chungpub/items/1.0056425

Post a Comment

Post a Comment